As we witnessed during the 2020 election season, and as we are sure to witness during the upcoming holiday season, the United States Postal Service doesn’t exactly instill confidence.

That’s not surprising, given that most of what the government provides or funds is inefficient. Think about it: do you take better care of your home or a hotel room?

The same principle applies to governments, which take other people’s money in the form of taxes and are therefore more likely to spend it wastefully than are citizens with their own money.

Luckily for us, private companies like FedEx and UPS provide alternatives for sending mail. If you’ve ever bought something like an expensive watch or ounce of gold online, the company you bought from probably chose to ship with someone other than the USPS.

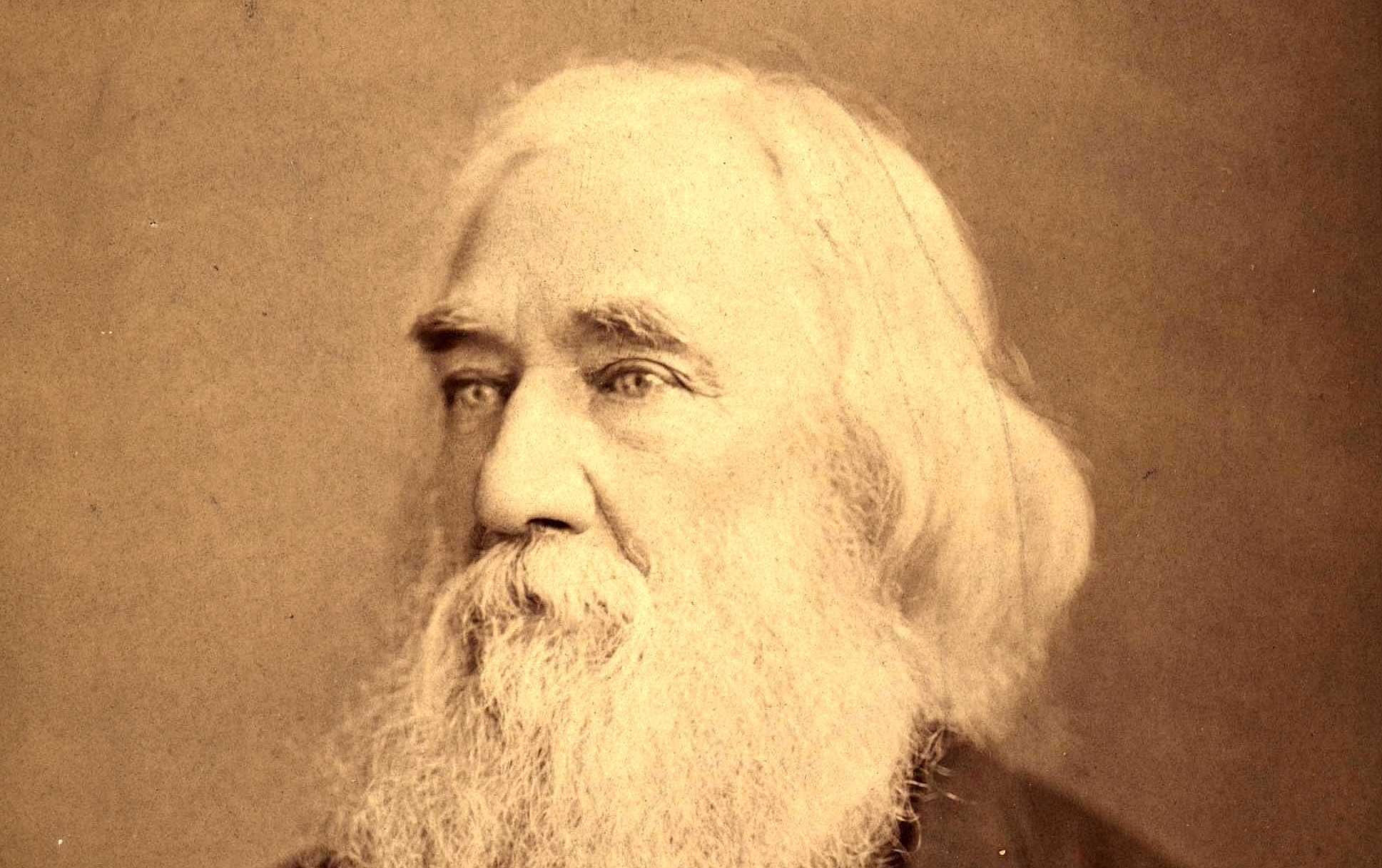

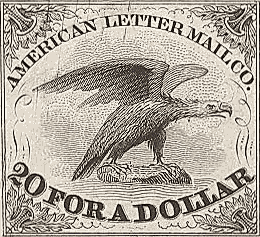

But the OG private competitor to the USPS was the American Letter Mail Company, founded in 1844 by Lysander Spooner, a lawyer and writer from Massachusetts, who became known as The Father of the Three-Cent Stamp.

Spooner was no stranger to the law — or to rebellion against it. In the 1830s, Massachusetts law required college graduates to apprentice with licensed attorneys for three years, while non-college graduates had to apprentice for five. Because a college education was then (as it is now) quite expensive, he considered the different requirements to be state-sponsored discrimination against the poor.

(That law, which was repealed soon after Spooner’s defiance of it, was far from the only way the state discriminates against the poor):

Spooner, who did not graduate from college, went ahead and set up a practice after only three years of apprenticeship. He wrote, “No one has yet ever dared advocate, in direct terms, so monstrous a principle as that the rich ought to be protected by law from the competition of the poor.” (His style of writing was more formal than Frederic Bastiat’s or Thomas Sowell’s, but his points were no less profound.)

Spooner’s background in law led him to realize that the Constitution ordered Congress to deliver mail, but that it never said private citizens couldn’t.

His American Letter Mail Company drastically undercut the Post Office’s prices. In 1844 when Spooner started his company, it cost almost 19 cents to send a letter from Boston to New York. A year later, the Post Office, forced to compete for the first time, cut its rates to match Spooner’s at five cents.

It only took about seven years for the Post Office to grow tired of competing. Congress enacted a law in 1851 to make the government’s monopoly on first-class mail (less than 13 ounces in weight) official. That was the last straw for Spooner; the Post Office’s built-in subsidies and continued harassment of the ALMC ran him out of business — but not until postal rates were cut again, to three cents.

As political and historical columnist Lindsey Williams wrote, “Philatelists [stamp collectors] periodically petition the government to issue a 3-cent stamp commemorating Lysander Spooner. However, the government is a sore loser.”

Despite his impact on postal rates, and although Spooner wrote and campaigned passionately for the abolition of slavery and for peace during the Civil War, we wouldn’t know his name today if not for his magnum opus: an ironclad takedown of the U.S. Constitution (and, more generally, Social Contract Theory) called No Treason: The Constitution of No Authority.

It’s almost too brilliant to summarize; we encourage you to read it for yourself. But in brutally logical and legal language, it reasons:

- -The Constitution only applies to the people who signed it;

- -They had no power to bind anyone else to it (especially future generations);

- -The act of voting binds nobody to the results of an election except a) people permitted to vote, who b) actually do vote, for c) the winner of the election. And that even those people, because all votes are cast by secret ballot, are not bound to the results;

- -And that the payment of taxes does not imply support of the government.

As he argued, the use of force to compel the payment of taxes is illegitimate and immoral. For what it’s worth, students at California State University-Northridge largely agreed:

“It is perfectly evident,” Spooner wrote, “that neither such voting, nor such payment of taxes, as actually takes place, proves anybody’s consent, or obligation, to support the Constitution. Consequently, we have no evidence at all that the Constitution is binding upon anybody, or that anybody is under any contract or obligation whatever to support it.”