This is the second of Learn Liberty’s “Legends” series. Read our first, on Ayn Rand, HERE.

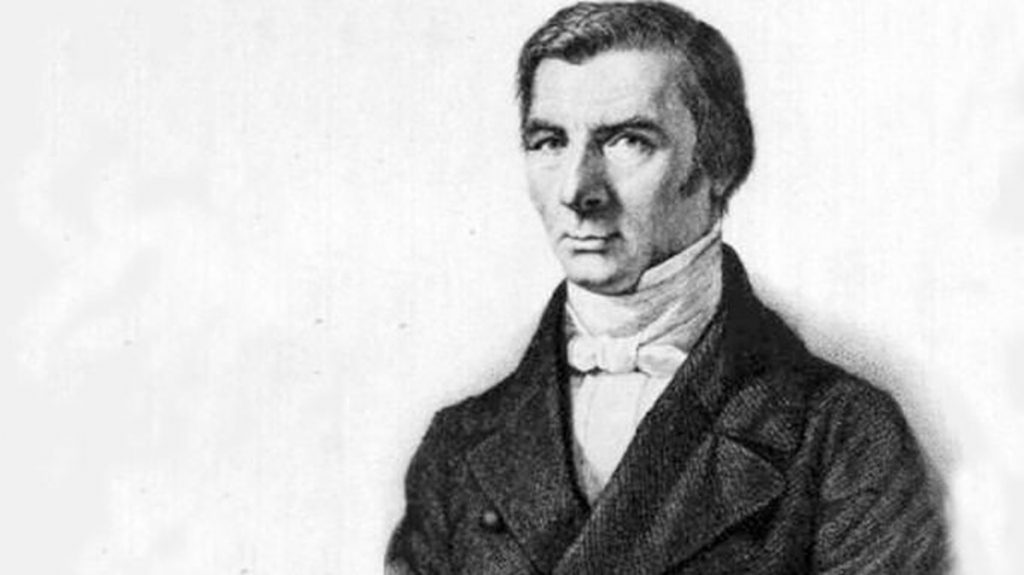

He never won a Nobel Prize.

He never wrote a New York Times bestseller. In the history books, he doesn’t sit alongside Adam Smith, Ludwig von Mises, and Friedrich Hayek as all-time great economists. He doesn’t even have an economic law named after him.

But Frederic Bastiat was a prolific writer, inventive social scientist, and above all, a brilliant champion for individual freedom. Indeed, Joseph Schumpeter, one of the 20th century’s foremost economists himself, described Bastiat as “the most brilliant economic journalist who ever lived.”

As you know if you’ve ever read Charles Dickens or Herman Melville — let alone Shakespeare — the language of the past can be difficult to understand. It’s often more formal than we’re used to and includes long sentences and old-fashioned words that are no longer part of our vocabulary. When you add the fact that economists tend to write in great detail about complicated subjects … well, you’ll be forgiven if The Wealth of Nations isn’t your preferred beach reading.

But Bastiat’s greatest strength was an ahead-of-his-time ability to simplify difficult ideas — and to make them cutting and funny.

The best example is his “Petition of the Candlemakers.” In a satirical petition to the French government that serves as a takedown of protectionism, he wrote:

“We [candlemakers] are suffering from the ruinous competition of a foreign rival who apparently works under conditions so far superior to our own for the production of light, that he is flooding the domestic market with it at an incredibly low price. This rival … is none other than the sun.

We ask you to be so good as to pass a law requiring the closing of all windows, skylights, inside and outside shutters, curtains … in short, all openings, holes, chinks, and fissures.”

His best-known work, “That Which Is Seen, and That Which Is Not Seen,” published in 1850, saw the debut of a crucial economic idea: opportunity cost (though it wasn’t called that until much later.) The idea is, when you buy a coffee for $3, you’re not just giving up $3; you’re also giving up something else that you could have bought with that money, had you not decided on coffee.

Bastiat illustrated this idea in his “Parable of the Broken Window,” which comprises the first section of “That Which Is Seen, And That Which Is Not Seen” and reflects on unintended consequences.

Imagine a shopkeeper’s son breaks one of the shop’s windows, Bastiat writes. The shopkeeper must pay a glazier, say, $6 to fix it. Some economists — not to mention everyday citizens — have assumed that breaking windows is, therefore, a good thing because it forces money to circulate.

That’s the part which is seen.

After all, if no windows were ever broken, no glaziers would have jobs, and wouldn’t that be sad?

Not really.

Because that which is not seen is what the shopkeeper would have spent his $6 on, had he not needed to pay for a new window. That $6, writes Bastiat, might have gone toward a new hat for the shopkeeper. In our time, that $6 could go toward any number of things — a cheeseburger, a movie ticket, a day pass at the local gym. We only get to see the glazier’s increased income as a result of the broken window; we never get to find out at whose expense it comes.

In 2011, Nobel Prize-winning economist Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking, Fast and Slow became a worldwide bestseller. It owes a debt of gratitude to Bastiat; the underlying current throughout the book is:

What you see is all there is.

That is to say: we tend to make decisions based on the information we have available, while we struggle to consider what information we lack.

Bastiat’s analysis of broken windows is perhaps best applied in modern times to the following unfortunate line of reasoning: that war is good for economies because it increases the manufacturing of goods and provides jobs to thousands of people. After all, if there were no war, all those soldiers, bullet makers, and tank builders would be out of work … right?

Nothing could be further from the truth. As we touched on in The Afghanistan Fiasco, Explained, because war is, inherently, destruction — of property and of lives — it damages the economies of all involved.