Laws Banning Alcohol and Drug Use

The abuse of alcohol and drugs has led to untold problems throughout American history. Colonial Americans sought to regulate alcohol, and in the 19th century, a powerful movement arose to ban it altogether. In 1919, the U.S. Constitution was amended to effectively prohibit alcohol. Congress passed the Volstead Act the same year to implement this amendment. Of particular interest is Congress’s approach to the issue of sacramental wine.

Sensitive to the reality that wine is used for the Eucharist (also known as Communion) and other religious ceremonies, Congress crafted an exemption to the Volstead Act. The language of Title II, Section 6 of the law begins:

Nothing in this title shall be held to apply to the manufacture, sale, transportation, importation, possession, or distribution of wine for sacramental purposes, or like religious rites. . . No person to whom a permit may be issued to manufacture, transport, import, or sell wines for sacramental purposes or like religious rites shall sell, barter, exchange, or furnish any such to any person not a rabbi, minister of the gospel, priest, or an officer duly authorized for the purpose by any church or congregation, nor to any such except upon an application duly subscribed by him, which application, authenticated as regulations may prescribe, shall be filed and preserved by the seller.”]

The text of the bill makes it clear that Congress was committed to protecting religious beliefs held alike by large denominations (e.g., Roman Catholics) and small religious bodies (e.g., Jews) who believed that sacramental wine should be used in religious ceremonies.

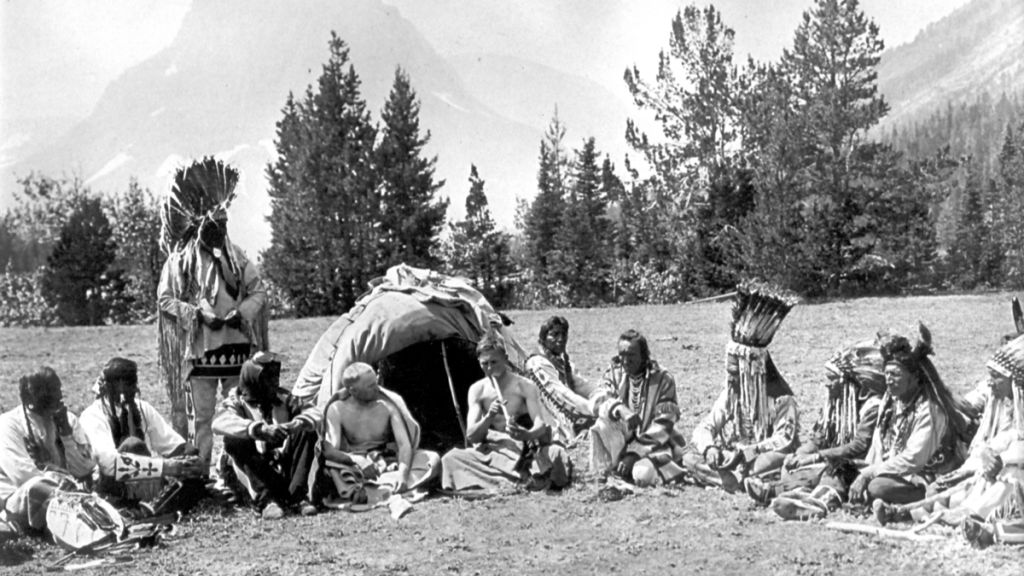

Far more difficult for legislators and courts have been the claims of citizens who contend that the use of regulated substances is part of their religious practices. Particularly well-known is the case of Native Americans who use peyote in religious ceremonies. Although peyote is a controlled substance, the national government recognized its legitimate use in “bona fide religious ceremonies of the Native American Church” in 1966. Some states adopted similar accommodations, but Oregon did not.

In Oregon v. Smith (1990) the Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment does not shield Native Americans or others who use peyote in religious ceremonies from neutral, generally applicable laws. Shortly after Smith was decided, Oregon passed a statute protecting the right of individuals (not just Native Americans) to use peyote in religious ceremonies. In 1994, without any recorded objections, Congress amended the American Indian Religious Freedom Act to protect Native Americans in the 22 states that did not permit Native Americans to use peyote in religious ceremonies.

At different times and in different ways, the national and state governments have attempted to prohibit alcohol and certain drugs. There have been extensive debates about the efficacy of these endeavors, but there is no reason to believe that accommodations crafted by legislatures to permit the sacramental use of wine, peyote, or other controlled substances by religious citizens have been detrimental to public health. From a historical perspective, these accommodations fit well with similar laws crafted to protect religious practitioners.

This is the seventh installment in a series by Mark Hall on religious freedom. Check out the previous installments below.

- Some Reflections on Whether We Should Abandon Religious Liberty

- Protecting Religious Liberty and the Common Good Aren’t Mutually Exclusive

- A History of Accomodating Religious Objections to War

- Oath Taking and Religious Liberty in American History

- How the Amish Led the Fight Against Compulsory Schooling

- The Right to Sit During the Pledge of Allegiance