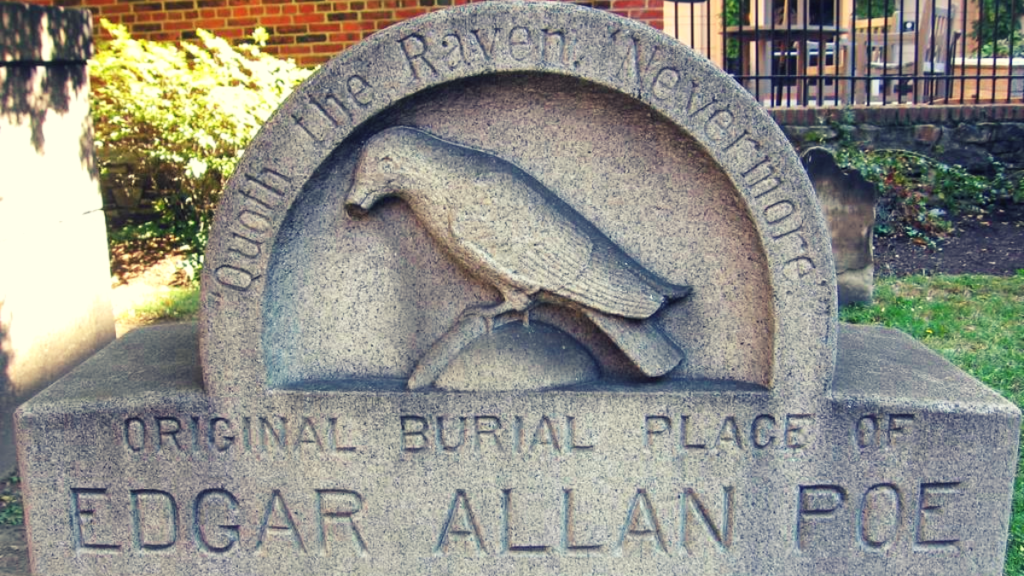

January 19, 2017 is the 208th birthday of literary great Edgar Allan Poe.

He doesn’t look a day over 40.

Chances are you’re familiar with at least some of Poe’s greatest hits: poems such as “The Raven” or “Annabel Lee,” for example, or stories like “The Tell-Tale Heart” or “The Fall of the House of Usher.” It’s worth our time to take a look at one of Poe’s less well-known works, however, to appreciate just how much Poe still has to say to readers today.

Mellonta Tauta: The Present as Future Past

Poe’s satirical dystopian science-fiction story “Mellonta Tauta” (“Things of the Future”) first appeared in Godey’s Lady’s Book in February 1849. Poe died later that year, and it’s fitting that this, one of his final published works, focuses on the fleeting and faulty nature of memory.

“Mellonta Tauta” takes place in the year 2848. Its narrator, “Pundita,” pens a rambling letter to a friend while moving at remarkable speed via balloon, a voyage that seems fantastic to the reader but “odious” to the bored traveler. As Pundita’s mind wanders from topic to topic, the reader learns more about the future — and how little its citizens understand of our shared past and values.

Poe’s wicked humor and pointed criticisms of everything from the politics to the fashions of his day can make this a challenging read — which is itself something of an irony, given its theme of how quickly we lose touch with our past — but “Mellonta Tauta” is well worth the effort, because Poe leaves us with a couple of sobering and timeless takeaways.

Takeaway #1: Ideas that we in our complacency assume are permanent (or at least long term) are, in fact, ephemeral, if we don’t take pains to preserve them and the history that informs them.

One of the funniest portions of Poe’s story is also one of the most disturbing. While “digging in the centre of the emperor’s garden,” workers discovered a long-buried monument from Yorktown celebrating the conclusion of the U.S. War of Independence from England.

This Corner Stone of a Monument to the

Memory of

GEORGE WASHINGTON,

was laid with appropriate ceremonies on the

19TH DAY OF OCTOBER, 1847,

the anniversary of the surrender of

Lord Cornwallis

to General Washington at Yorktown,

A. D. 1781,

under the auspices of the

Washington Monument Association of the

city of New York.

In the absence of memory of the Revolution, of the United States, or of the ideas that helped lead to both, the learned Pundita is left to interpret this discovery as a commemoration of one man’s surrender to a cannibalistic group of cornerstone-layers so that he could be made into sausage for them:

We ascertain … from this admirable inscription, the how, as well as the where and the what, of the great surrender in question. As to the where, it was Yorktown (wherever that was), and as to the what, it was General Cornwallis (no doubt some wealthy dealer in corn). He was surrendered. The inscription commemorates the surrender of — what? — why, “of Lord Cornwallis.” The only question is what could the savages wish him surrendered for. But when we remember that these savages were undoubtedly cannibals, we are led to the conclusion that they intended him for sausage. As to the how of the surrender, no language can be more explicit. Lord Cornwallis was surrendered (for sausage) “under the auspices of the Washington Monument Association” — no doubt a charitable institution for the depositing of corner-stones.

Takeaway #2:The belief that people naturally will become better can be a dangerous thing.

Poe strongly disagreed with the idea of human perfectibility that emerged from the Enlightenment, and thus he paints a sharp contrast between the technological marvels of the future in “Mellonta Tauta” and the Hobbesian brutality of people’s everyday lives. Without institutions in place to limit power and promote individualism, the future Poe gives us has become a nightmare in which rulers thrive and other human lives no longer matter.

The travelers on Pundita’s balloon watch without concern or empathy as a man who falls overboard is left to drown, simply because it would be inconvenient to try to save him. Why bother?

In a particularly telling passage, Pundita writes,

We lay to a few minutes to ask the cutter some questions, and learned, among other glorious news, that civil war is raging in Africa, while the plague is doing its good work beautifully both in Yurope and Ayesher. Is it not truly remarkable that, before the magnificent light shed upon philosophy by Humanity, the world was accustomed to regard War and Pestilence as calamities? Do you know that prayers were actually offered up in the ancient temples to the end that these evils (!) might not be visited upon mankind? Is it not really difficult to comprehend upon what principle of interest our forefathers acted? Were they so blind as not to perceive that the destruction of a myriad of individuals is only so much positive advantage to the mass!

By looking at our present as the future’s misremembered past, Poe allows us to consider the world we’re in the process of making — before that future world, like the Yorktown monument, is set in stone.

Want more to explore?

Check out the resources below.

- The complete “Mellonta Tauta.”

- My unabridged reading of “Mella Tauta.” [Download]

- PoeStories.com: An Exploration of Short Stories by Edgar Allan Poe (This site contains short stories and poems by Edgar Allan Poe as well as summaries, quotes, and linked vocabulary words and definitions for educational reading. It also includes a short biography, a timeline of Poe’s life, and links to other Poe sites.)

- The Poe Museum of Richmond

- The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore

- The Goodreads Interactive List of “Fiction Featuring Poe as a Character.”

- “Mysterious for Evermore,” by Matthew Pearl, in the Telegraph. (This article explores Poe’s unsolved death. Pearl is also the author of a fascinating novel about the subject, The Poe Shadow.)