What American universities are doing to economics students is shameful. I can’t speak to universities in other countries, but I’ll bet the same applies in most of them.

When I was a freshman in college, for example, I enrolled in a class called Econ 1051. I wasn’t interested in economics; it was just a prerequisite for my journalism major, but obviously I still wanted to do well.

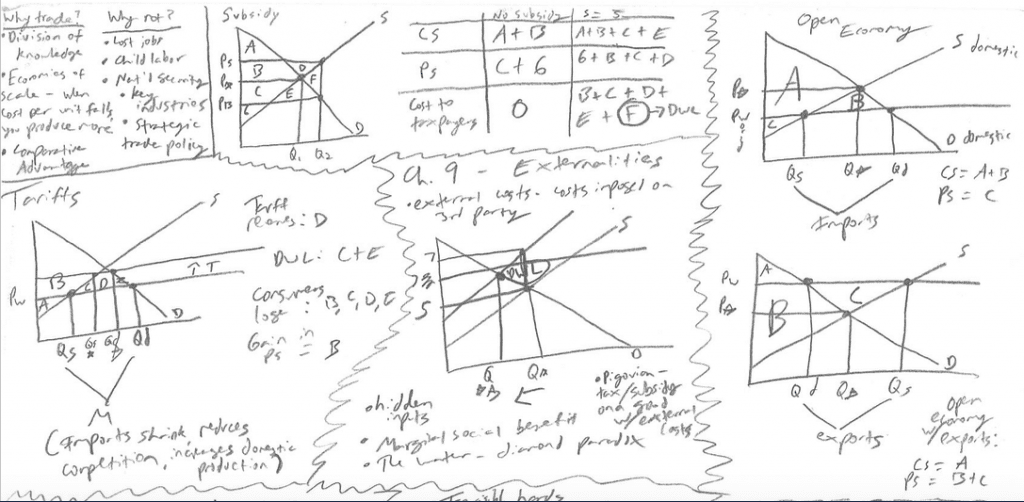

I still have many of my notes from that class. Here’s the study guide I put together for an exam:

I’m pleasantly surprised to see some mention of concepts like division of knowledge/labor, comparative advantage, and economies of scale there in the upper-left.

But as I write here, 13 years later, it’s no surprise that my broad takeaway from that course is: graphs. Lots and lots of graphs.

Coupled with a strong dose of equations for things like the elasticity of supply and the Laffer Curve (R = τ(z0(1 – τ)ε – b), those graphs portray economics as something closer to math than social studies.

That’s why, if you type “does economics” into Google, the top autofill options are: “involve math” and “count as social studies.” (Another common Google autofill is: “how do economists use graphs?”) But there’s a crucial, unavoidable difference between economics and math.

Why economics is not math

In mathematics, constant relations not only are possible, but exist. 10 was one more than 9 in the year 1922, just as it is here in 2022. And 10 will be one more than 9 a century from now, too. That fact will never change. The relationship between the numbers 10 and 9 is constant.

Physical consistency, expressed through mathematics, allows us not just to predict the future, but in some sense, to know it. If, for example, I drop a tennis ball off my balcony, I know it will fall. I know how fast it will fall, too: 9.8 m/s^2.

That mathematical consistency is what we come to expect from economics when it’s taught to us predominantly with equations and graphs. And that expectation of consistency empowers politicians and bureaucrats (who are almost always graduates of universities) to promise that if only they’re allowed to tinker with policy and law in the ways they see fit, it will lead to “the greatest good for the greatest number.”

However, in economics, constant relations not only are not possible, but can’t exist. Because economics involves the behavior of human beings, not numbers or inanimate objects.

Relationships among humans begin, they develop, they get strained, they end. Sometimes they restart, re-develop, and so on. I do not have the same relationship with my younger brother as I did on the day he was born. I don’t buy the same things at the grocery store that I did as a freshman in college.

Heck, I once had lunch in a restaurant in Madrid, Spain, called La Gloria in 2019 — simply because a song of that name, released in 1982, had surged in popularity in my hometown of St. Louis, Missouri.

What equation could predict that economic transaction between me and the restaurant owner: 25 euros in exchange for a meal? What graph could tell us to expect a minuscule increase in demand for La Gloria’s food in 2019?

I wish I had been more interested in economics when I was a student, and I wish I had understood that human relationships constantly change. That’s on me.

But I also wish economics professors would ditch the equations, graphs, and textbooks, ditch the fallacious appeal to constant relationships, and talk about what economics really is: mostly unpredictable, ever-changing human behavior in a messy world of trade-offs, incentives, and competing interests and desires.

To hear logical, clear, graph-free answers to some of the web’s most-googled questions, including, “Does economics count as social studies?” check out our video below:

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the organization as a whole. Students For Liberty is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions.